Do Something… ANYTHING!

“… so we are doing everything we can.” This was the concluding statement in a meeting I once attended. The presenter had just finished explaining how audience attendance was down by double-digit percentages and the lead fundraising event had lower-than-expected turnout. With these looming, end-of-year results, the presenter outlined a mix of repeated strategies that hadn’t worked and a few superficial ideas chasing social media trends.

The statement was met with understanding nods. At least we were doing something. The mood in the room spoke of an unspoken confession: No one knew what might turn this around.

“Doing everything we can” echoed several more times in meetings during my career. It reminded me of research I encountered years ago.

More Focus, Less Activity: How Action Bias Undermines Strategic Growth

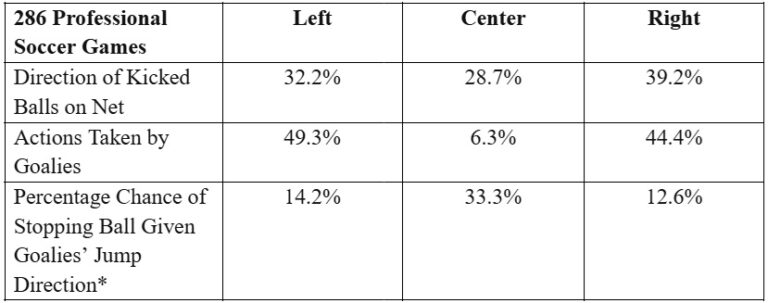

Researchers studying penalty kicks in professional soccer found a psychological tendency among elite goalkeepers. With milliseconds to decide whether to dive left or right—essentially deciding before the ball is kicked—goalkeepers often act counterproductively (Bar-Eli et al., 2007; Chiappori et al., 2002; Palacios-Huerta, 2003).

*This percentage will not total 100% as it is calculated as the number of kicks stopped divided by the total number of kicks for each kick-jump combination.

Analyzing 286 penalty kicks, researchers found the direction of the kicked balls was evenly distributed: 32.2% left, 28.7% center, and 39.2% right. The chance of stopping the ball when diving left, staying center, or diving right was 14.2%, 33.3%, and 12.6%, respectively. Despite this, goalkeepers dove left 49.3% of the time, stayed centered only 6.3%, and dove right 44.4%.

Statistically, goalkeepers are better off staying in the center. Yet, under pressure, they often dive—an instinct driven by “action bias,” the urge to act even when doing less is the optimal choice. After all, it’s easier to justify diving than appearing passive as a ball sails past.

Doing All the Things, But Missing the Goal

Action bias isn’t limited to sports. In the arts and cultural sectors, it shapes decisions in unhelpful ways. When faced with shrinking audiences or funding, organizations often respond by doing more: More social media posts, more events, more promotions. However, like a goalkeeper’s instinct to dive, this reaction is not always strategic.

The Case for “Staying Centered”

Staying centered means positioning yourself where you’re most likely to succeed. What does this look like for struggling arts organizations? Here are three ideas:

- Build the Audience You Have: Too often, organizations invest in expensive platforms that don’t suit their needs. Simple, inexpensive technology can achieve powerful results when implemented with a clear understanding of your audience’s needs.

- Focus on Value, Not Volume: Highlight the benefits of your work, not just its features. Instead of emphasizing “50 concerts this season,” emphasize the impact: “Be inspired and step back into your world renewed.”

- Evaluate Outcomes, Not Effort: Success isn’t measured by activity but by results. Like a goalkeeper’s job is to stop goals, organizations should tie every action to clear outcomes. This requires discipline but is crucial for impact.

It’s easy to criticize a goalkeeper who stays still or a leader who says, “Let’s do less, but do it better.” Yet, the research shows it’s best to resist the urge to act if you have not clearly defined the steps back from a clearly reasoned outcome (Dixit & Nalebuff, 2008).

I see too many organizations adopting activities without designing strategies unique to their growth pathways. They risk becoming busy but ineffective. At the end of the day, success isn’t about how impressive your dives look. It’s whether you’re achieving what you’ve set out to do.

Bar-Eli, M., Azar, O. H., Ritov, I., Keidar-Levin, Y., & Schein, G. (2007). Action bias among elite soccer goalkeepers: The case of penalty kicks. Journal of Economic Psychology, 28(5), 606–621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2006.12.001

Chiappori, P.-A., Levitt, S., & Groseclose, T. (2002). Testing mixed-strategy equilibria when players are heterogeneous: The case of penalty kicks in soccer. American Economic Review, 92(4), 1138–1151. https://doi.org/10.1257/00028280260344678

Dixit, A. K., & Nalebuff, B. J. (2008). The art of strategy: A game theorist’s guide to success in business and life. W. W. Norton & Company.

Palacios-Huerta, I. (2003). Professionals play Minimax. Review of Economic Studies, 70(2), 395–415. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-937X.00249

Savelsbergh, G. J. P., Van Der Kamp, J., Williams, A. M., & Ward, P. (2005). Anticipation and visual search behaviour in expert soccer goalkeepers. Ergonomics, 48(11–14), 1686–1697. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140130500101346