Fishing for Complements: A Clarifying Framework

Last week, I suggested that effective communication consisted of two elements:

Effective Communication = What You Say + How You Say It

While “how you say it” is widely supported with tools, structures, platforms, and pre-packaged knowledge, “what you say” remains deeply personal and individualistic. It’s no surprise there’s a comparative dearth of tools—or even meaningful YouTube videos—on the subject. That gap makes getting “what you say” clear and powerful more important than ever. It takes a purposeful, introspective wrestling. And a good deal of coaching, practice, and work. Yet higher music education institutions haven’t fully picked up on this need. (And judging by the comments, in many other career areas and disciplines, too.)

When I mentioned the equation, I thought back to a conversation I had with Ajay Agrawal over lunch almost ten years ago. We tackled all sorts of topics ranging from the economies of technology, competitive advantages in creative industries, and the then-nascent impact of artificial intelligence.

Ajay saw the relevance of AI long before most people did, and I’ve always been struck by his ability to distill complex ideas into simple, clear insights.

During our conversation, I admitted struggling to see how AI would directly impact the classical music industry. (At the time, I was a vice president at the Toronto Symphony Orchestra.) I felt as if a spotlight hit our table at the university faculty club.

He put down his fork.

“I think AI is going to influence just about everything.”

But what stuck with me most was his argument that music, art, and human creativity itself would take on a new significance. He then walked me through an early concept that would later appear in his book Prediction Machines (co-written with Joshua Gans and Avi Goldfarb).

They propose that AI’s role can be understood through the lens of decision-making:

Decision-making = Prediction + Judgment

Prediction = Estimating the likelihood of an event occurring.

Judgment = Deciding how to respond to that likelihood.

AI, Ajay explained, was about to make prediction much cheaper and more accessible, fundamentally shifting the decision-making equation.

Take coffee, for example. He explained, “If coffee suddenly became much cheaper, people would buy more of it. And for those who don’t take their coffee black, its complements—like milk and sugar—would rise in value.”

In the same way, as AI lowers the cost of prediction, judgment becomes more valuable than ever.

Exercising Backhanded Complements

“Taste is a skill” (Godin, 2020.)

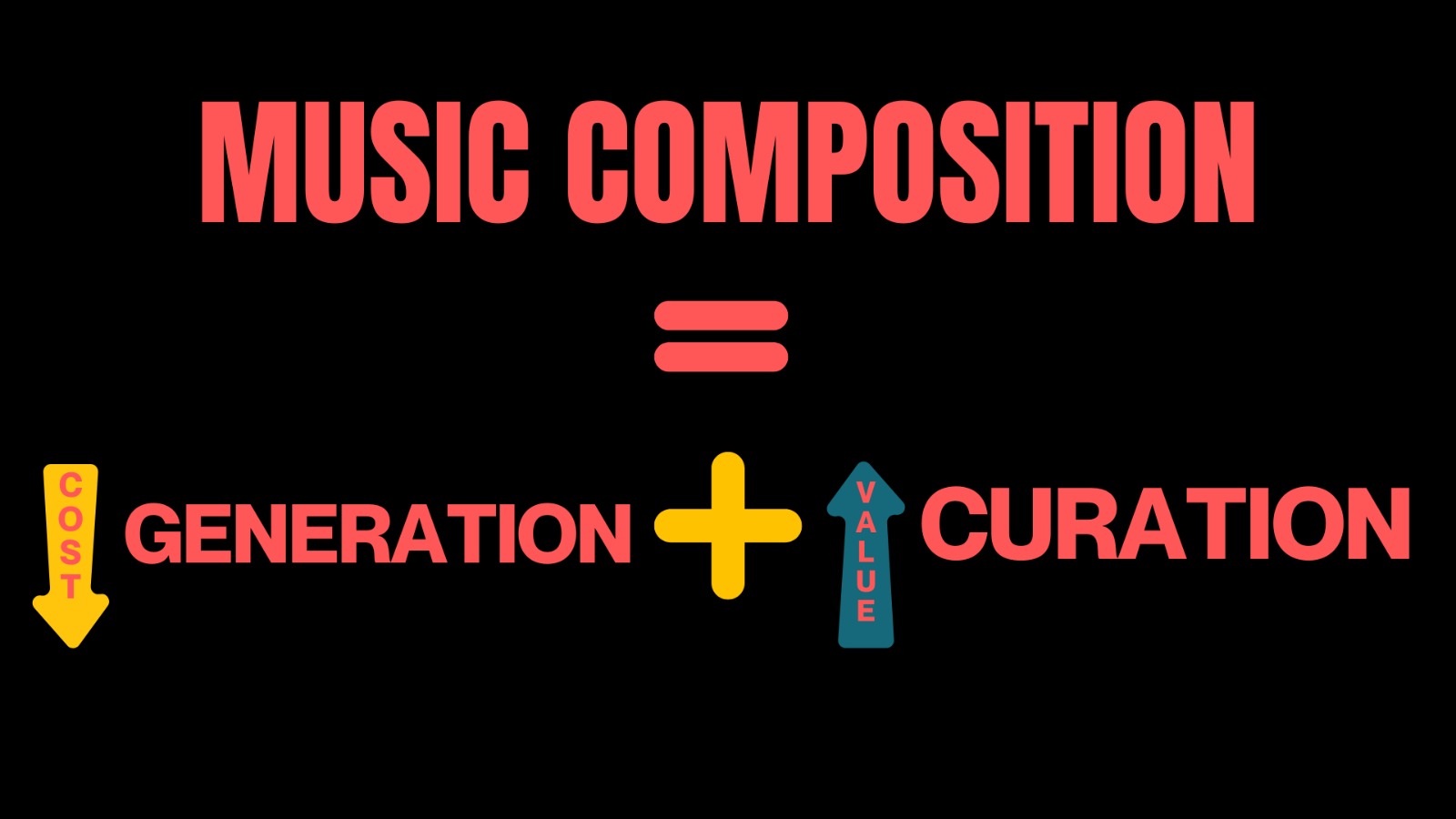

The equation made me think about how AI is affecting music on the level of composition, and how we might understand it with a complementarity equation I created as an exercise below.

In the past, composing music required an immense investment of time, education, and labor. A composer had to master harmony, counterpoint, and orchestration, spending years refining their craft before they could bring their musical ideas to life. In short, it was expensive and altogether time-consuming. Today, AI software can generate harmonies, suggest chord progressions, and even compose entire pieces from scratch. What once took years of training can now be done in seconds with the click of a button.

One might say AI made composition easy. At first glance, this might seem like a revolution—democratizing composition, making music creation accessible to more people.

But it only makes only one part of the equation easy.

Composition = Generation + Curation

And it shifts the nature of real talent. AI may have made the process of creating raw musical material like melodies, harmonies, and structures (“generation”) more effortless. But the act of choosing, refining, and shaping what is meaningful (“curation”) remains the domain of human expertise, intuition, and artistry.

If software can generate endless musical options, then the hardest part is not producing music—it’s choosing the right music. The true skill may not be in creating a melody (because AI can do that too), but in knowing which melody is worth keeping, which harmony enhances meaning, and which choices create something truly moving.

If you’re an artist, you have likely heard how we need to “murder our darlings.”** We’ve always needed to leave certain sinews of our creations on the cutting room floor. The value of our “selection” process is a muscle that gets more of a workout now.

That’s a good thing: Though it was always important, it’s more important than ever.

The Talent Is In The Curation

“The talent is in the choices” (Adler, 2000.)

I’m reminded of when Excel (and Lotus 1-2-3) were introduced: There was a pervasive fear that accountants and bookkeepers would become obsolete. But instead of making them irrelevant, these tools made accountants better. Far from being obsolete, they could now handle more clients, more effectively, and likely provide better insight and advice. Technology didn’t eliminate them—it reshaped the field, raising the value of judgment and expertise.

When Ajay and I spoke about AI 10 years ago, many artists did not think it would apply to us. Many harboured a fear or icky feeling about AI. Today, I believe many of us still do. But it helps to see AI’s contribution in an objective complementarity equation.

It doesn’t diminish human artistry—it makes it more important than ever.

*Decision-making has been expressed as comprising of prediction and judgment in the past (explicitly: Mosier, 2013; Mosier & Fischer, 2010; implicitly: Brunswik, 1943; Kahneman et al., 1982).

**Often misattributed to Faulkner or Hemingway, “murder your darlings” came from Arthur Quiller-Couch in 1916.

Adler, S. (2000). The art of acting (H. Clurman & K. Paris, Eds.). Applause Theatre & Cinema Books.

Agrawal, A., Gans, J., & Goldfarb, A. (2018). Prediction machines: The simple economics of artificial intelligence. Harvard Business Review Press.

Brunswik, E. (1943). Organismic achievement and environmental probability. Psychological Review, 50(4), 255–272. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0060889

Godin, S. (2020). The practice: Shipping creative work. Portfolio.

Kahneman, D., Slovic, P., & Tversky, A. (Eds.). (1982). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Cambridge University Press.

Quiller-Couch, A. (1916). On the art of writing. Cambridge University Press.

Mosier, K. L. (2013). Judgment and prediction. Oxford University Press.

https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199757183.013.0005

Mosier, K. L., & Fischer, U. M. (2017). Judgment and decision making by individuals and teams: Issues, models, and applications. In D. Harris & W.-C. Li (Eds.), Decision Making in Aviation (1st ed., pp. 139–198). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315095080-7