The Power of Limitations

“The enemy of art is the absence of limitations.” — Orson Welles

It had been a whirlwind two weeks of work and travel. And things almost ground to a halt when a recurring health issue reared its familiar and ugly head a few days ago: This medical condition affects my ability to walk.

At the worst points, this condition has left me bedridden for months. I’ve learned and adopted various adjustments which have allowed me to cope. Most of the time, people don’t even notice any disability. This hasn’t been the case this time around with the arrival of a new (or a new expression of the same old) issue.

As I was hobbling, a long-time colleague noted that I was smiling; he marveled that I seemed “grateful” despite the experience.

This comment surprised me. I wasn’t feeling particularly grateful.

But I’ve realized that, in a way, I am. Not because I enjoy the pain, but because I’ve learned to look for what these limitations give me. When one door closes, another pathway—one I wouldn’t have noticed otherwise—opens.

This isn’t meant to romanticize pain or dismiss its challenges. But in acknowledging setbacks, I’ve also learned to capitalize on other ways of solving problems.

Why Constraints Matter

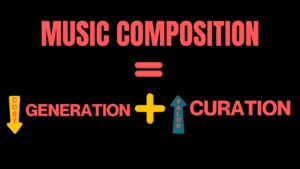

In my work as a producer and cellist, I have often sought out creative limitations.

This isn’t new to musicians. In my cello practice, creating limitations through exercises—playing a passage using only one bow direction, or using only one string, or never getting louder than a certain volume—has been a source of insight. It improves my technical playing by isolating and evaluating aspects which help or hinder my progress. It improves my understanding by playing something “wrong” in order to see what makes a composed passage “right.”

Sometimes, these exercises even lead to entirely new interpretations—because they force me to rethink how I play.

I’ve always believed that when we have no boundaries, we get stuck traveling the same old ruts. We tend to default to what’s familiar: No surprises, no friction, no fresh perspective. It’s only when we impose constraints that our best, most imaginative work arises.

Sometimes, those constraints are self-imposed. Other times, as I’ve been reminded this week, they’re thrust upon us.

At a certain point, I realized that being bedridden could go two ways:

- I could stew about it, spiraling into restless frustration.

- Or I could take the opportunity for quiet, thoughtfulness, and focus.

It was near impossible some days. But, if I’m honest, the struggle has had its rewards: I would not have been able to start two companies and complete a doctorate had I not taken advantage of the forced “incubation.”

The Restrictions in Rhymes

When I was a teenager, I read Orwell’s 1984 that there were only 12 perfect rhymes for “God” in English. Out of hundreds of thousands of words, there were only a dozen perfect rhymes.

Rhyme is a limitation, and limitations create difficulty. The fact that rhymes are hard fascinated me. The general population doesn’t witness Eminem rattle off reams of multisyllabic rhymes without having some inkling at its difficulty. Part of the magic is that we know how hard it is. It takes design and skill to work within the constraints of rhyme and rhythm—and that’s what makes it impressive.

The same is true of Shakespeare. He wasn’t just making up stories—he was writing inside strict structural rules. He had to fit meaning within meter, create compelling metaphors, and shape natural speech into poetic form.

Perhaps Shakespeare was able to achieve such heights in his art because of these imposed limitations. Limitations themselves are like trellises—structures that allow plants, vines, or flowers to grow.

Limiting yourself in ways others don’t might mean you achieve things others never do.

Art forms like haiku, sonnets, and limericks rely on constraints. A haiku demands just 17 syllables, forcing the poet to strip away everything unnecessary. A sonnet locks you into a 14-line format with a strict rhyme scheme. Limericks have to roll off the tongue the right way. When I embark on limiting exercises or strategic thought experiments, I feel “trapped” at first, but that structure often pushes me towards something new.

And I’ve found there’s an adrenaline to this discovery.

Constraints Fuel Creativity

I’ve written in the last few weeks about the problem with higher education’s curricula across the fine arts.

A fine example is the mind-boggling number of fantastic string quartets coming up these days. Yet almost all of them hope for one thing: A teaching ensemble residency at a university. This makes sense because most of the world’s great string quartets have taken up these types of residencies.

But my friends in the legendary Kronos Quartet took a less-traveled path by avoiding the traditional university residency. By subtracting a standard choice, the Kronos filled that void with bold collaborations, distinct performances, and a rigorous organization that supported their increasingly visionary projects.

Perhaps their creativity flourished precisely because they chose not to rely on the norm.

Final Thought

Orson Welles nailed it. Without boundaries or rules, things can become stale. I’ve found embracing a limitation—maybe even one that seems “unfair”—has been helpful to my overall growth. I’ve been surprised how freeing it can be to paint myself into a corner. Maybe that’s where some of my best solutions have been found.

I didn’t choose this limitation. But I can choose how I respond to it. And as I’ve learned, even the constraints we resent can shape something greater than we ever imagined.

And the tricky part is, some of those boundaries are invisible. We follow routines without thinking. We accept limitations without questioning. We take certain paths because “that’s how it’s always been done.”

But if we can disrupt those patterns—either by imposing new constraints or embracing the ones forced upon us—we might find something better.

Maybe the leading question for me this week is: “What can I do precisely because I can’t do what I’ve always done?”

Rosso, B. D. (2014). Creativity and constraints: Exploring the role of constraints in the creative processes of research and development teams. Organization Studies, 35(4), 551–585. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840613517600

Chan, J., Fu, K., Schunn, C., Cagan, J., Wood, K., & Kotovsky, K. (2011). On the benefits and pitfalls of analogies for innovative design: Ideation performance based on analogical distance, commonness, and modality of examples. Journal of Mechanical Design, 133(8), 081004. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4004396

Moreau, C. P., & Dahl, D. W. (2005). Designing the solution: The impact of constraints on consumers’ creativity. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1086/429601

One Comment

[…] interpretation, but to dislodge ourselves from assumptions (see: “Beyond Perfection” and “Creative Limitations”). Like the upside-down drawing, this approach reveals hidden contours and details we may have […]