There’s an old story about a psychologist who placed five monkeys in a cage with a ladder leading up to a bunch of bananas. The moment a monkey climbed the ladder, the psychologist doused all the monkeys with cold water. Over time, every time one attempted to reach the bananas, the group would pull them down, having learned that climbing meant punishment. Eventually, the psychologist removed the water, but the behavior remained—no monkey dared climb. Then, one by one, the monkeys were replaced. Each new monkey, upon trying to reach for the bananas, was stopped by the others—despite never having been sprayed. By the time all five monkeys were new, none had ever experienced the cold water, yet they all still enforced the unwritten rule: Don’t climb the ladder.

Though this specific experiment never happened, the underlying behavior is real. A 1967 study by G.R. Stephenson found that rhesus monkeys, after being conditioned to avoid an object through an aversive stimulus, passed this fear onto naïve newcomers—who, despite never experiencing the punishment themselves, still learned to stay away. The lesson? Sometimes, we inherit limits without ever questioning them.

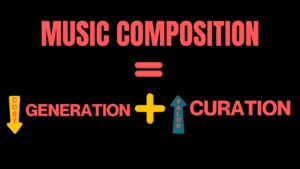

This, much like so many practices in our lives and industries, is a perfect metaphor for how we hold ourselves back—not because we’ve encountered the original barriers, but because we’ve inherited their echoes. I’ve often felt this when looking at the carefully prescribed pathways of conservatory training and higher education. My research from my doctoral dissertation corroborate these insights. I’ve found these structures, once designed to shape musicians for a world that no longer exists, still enforce old assumptions. The problem is the world has changed. The way music is made, consumed, and shared is shifting beneath our feet, and yet many are still following the rules of a game designed for an era long past.

Take the great composers—Bach, Haydn, Handel. They weren’t simply products of rigorous classical training; they were also entrepreneurs, improvisers, and risk-takers. In Leipzig, Telemann and his peers didn’t wait for someone to hand them a career. They built their own, navigating churches, courts, and cities with an awareness of their time. They climbed the ladder.

And yet, so much of our training still assumes that we must wait to be chosen. That we must slice off the edges of our careers, aspirations, and talents to fit into a mold designed generations ago. I’ll be writing about this more fully later, but the biggest part of my research was mined for studying present-day high-achieving entrepreneurial classical musicians.

The biggest cultural barrier is that we believe we must wait to be chosen. We audition and we wait for the jury’s acceptance or rejection. We compete and hope to place. We wait by our phones for a presenter to engage us. We aren’t trained in our minds to actively choose ourselves.

Worse off, sometimes, innovative musicians are quietly rebuffed as those who weren’t “good enough” to make it on the straight and narrow. Sometimes, we bristle at the idea of doing things differently. We roll our eyes at innovative programs that we feel pander to audiences. And, yes, there are bad examples coming from any approach. But if our best and brightest aren’t encouraged to think of new ways to approach these huge systems-level breakdowns in our industry, we are missing the point. We aren’t enriching the art the way our lauded and most celebrated musicians did.

I will be writing more in the future about areas higher education may have made a wrong turn with our curriculum.

But the wider learning may be that the biggest barrier isn’t the cold water. It’s the belief that it’s still there.

Stephenson, G. R. (1967). Cultural acquisition of a specific learned response among rhesus monkeys. In D. Starek, R. Schneider, & H. J. Kuhn (Eds.), Progress in Primatology (pp. 279–288). Stuttgart: Fischer.

One Comment

[…] musicians didn’t wait to be chosen. They carved out their own paths, launching exciting projects and stepping into new artistic […]