The Precedent Has Been Set

Though my goal this year is to write every day (and post at least three times a month), I’m already coming up against the wire. Some friends tell me I have a good excuse: five concerts, a recording, a knee issue, and, oh yes, a doctoral dissertation defense. But nothing drips quite as much of weakness as stumbling into a faceplant, making excuses through spluttered mud. “Happy New Yea—wait, I mean starting now.”

If I’m honest, I did write every day. I just convinced myself none of it was good enough. And that’s embarrassing to admit. Perfectionism can do that to you—it’s a sly thief of time and courage. Research backs this up: Jadidi et al. (2011) and Sederlund and Burns (2020) found that perfectionism often drives procrastination. The higher the standards we set for ourselves, the more likely we are to hesitate, delay, or simply freeze, afraid to start. Khosravi and Baghbani-Arani (2023) call this a cycle of anxiety, perfectionism, and procrastination—a trifecta that makes progress feel like an impossibility.

Ironically, I’ve taught an entire graduate course about the importance of getting off our duffs, railing against perfectionism as one of the most common culprits for not taking the first step. (Hopefully, my students don’t read this.) But if I’ve learned anything, it’s this: a good teacher has failed more times than their students have even tried.

The Perfection Hurdle

For musicians, aiming for “perfection” often results in nothing more than a clinical interpretation. And let’s face it: no musician is perfect. Audiences are smart. They know what you’re aiming for. If, as a cellist, your goal on stage is simply to play in tune, the audience will sense that. And when you inevitably fall short, it leaves them with a faint whiff of disappointment.

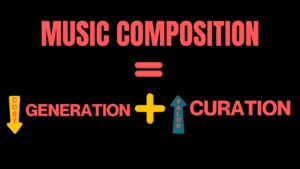

But when your goal is to say something, to create beauty, the stakes shift. Suddenly, perfection isn’t the goal—it’s just one tool in service of something greater. Chasing technical perfection is actually a shockingly low bar. When musicians aim for something “beyond perfect,” they naturally strive for all the elements perfection demands—correct notes, good intonation, “right” dynamics—but their focus extends far beyond those mechanics.

Race car drivers are focused on the driving; in performance, they shouldn’t be worried about the nuts and bolts holding their car together.

Lessons from Public Speaking

I think about this when reflecting on public figures. Does anyone remember George W. Bush’s verbal stumbles that grew more frequent and awkward toward the end of his presidency? Moments like “Is… our… children learning?” stand out. He seemed to freeze under the pressure of avoiding mistakes, and in trying so hard to be mistake-free, his pacing, tone, and message became stilted.

Then came Obama, who spoke with a keen sense of rhetoric, rhythm, and resonance. His speeches weren’t mistake-free either—far from it. But Obama always had a point, a trajectory, a destination. I’ll never forget seeing him laugh at his own verbal stumbles during a White House Correspondents’ Dinner. By embracing his imperfections, he revealed that his mistakes didn’t matter because people were captivated by where he was taking them. He aimed to say something, and that mattered far more than perfection.

Exploring Multiple Paths: Some of Them Backward

It wasn’t until my early 20s that I realized the futility of chasing “perfect” in my practice. Instead of playing a passage repeatedly in search of perfection, I started playing it in different ways—backward bowings, opposite dynamics, speeding up, slowing down, even improvising into double-stopped fourths. I wanted to understand why the composer structured it the way they did, and the only way to learn was to explore.

I explain it to my students like this: If you move to a new town and take the exact same route from home to work every day, how well will you know the city after a month? You might know the weather or the traffic patterns, but that’s about it. Now imagine you walked a different route every day—sometimes biking, sometimes taking a taxi, sometimes even riding a horse. You’d know your new hometown much better, wouldn’t you?

This principle is supported by the work of K. Anders Ericsson and his colleagues (1993), whose research on deliberate practice emphasizes the value of variability in learning. Their studies on contextual interference and variable practice suggest that exploring different approaches improves skill acquisition and retention.

The Fun Factor

But here’s where I disagree with Ericsson and his colleagues. They de-emphasized the role of fun, repeatedly stating that deliberate practice is exhausting, difficult to sustain, and “not inherently motivating” (Ericsson et al., 1993, p. 368). Great marketing!

For me, though, “fun” doesn’t mean frivolity. It’s about curiosity, creativity, and finding joy in the hard work. Cultivating fun doesn’t make the process less challenging—it makes it more sustainable and rewarding.

There’s always a fun and grim way to approach almost anything. Actively choosing the former has been a major mind shift in my practice. By embodying a playful spirit—whether improvising new ways to solve problems or simply exploring for the sake of curiosity—I’ve found a north star that guides how I approach music and my instrument. It’s not about ignoring the work; it’s about finding joy in the work is done.

Beyond Perfection

Whether it’s in writing, music, or public speaking, I’ve found the goal isn’t to get everything right—it’s to connect meaningfully with an audience. It’s hard to connect meaningfully when perfection distracts us from the bigger picture.

So after a false start, I’ve resolved to redouble my efforts. Writing, even when I’ve stopped, is like practicing a passage in music—sometimes messy, always revealing, and occasionally, meaningful.

I mean, starting now.

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.100.3.363

Jadidi, F., Mohammadkhani, S., & Zahedi Tajrishi, K. (2011). Perfectionism and academic procrastination. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 534–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.104

Sederlund, A., & Burns, L. R. (2020). Multidimensional models of perfectionism and procrastination. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 5099. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145099

Khosravi, M., & Baghbani-Arani, F. (2023). The triangle of anxiety, perfectionism, and academic procrastination. BMC Medical Education, 23(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05145-3

One Comment

[…] to arrive at a final interpretation, but to dislodge ourselves from assumptions (see: “Beyond Perfection” and “Creative Limitations”). Like the upside-down drawing, this approach reveals hidden […]